Just a dozen or so years ago, the only divisions that existed in Poland were light and dark. Alternatively, there were alcoholic and non-alcoholic, or regular and fruity. Since then, however, we’ve come a long way; craft beer has become commonplace, and today—like the rest of the world—we know that beer styles are incredibly diverse.

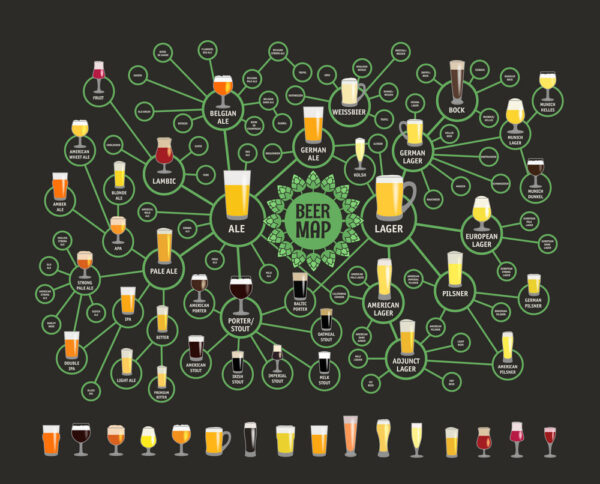

The global organization of beer judges, the BJCP , has listed over 120 different beer styles in its latest guide! And yet, there are still some that weren’t included in this guide—like the Cold IPA I recently reviewed. It’s safe to say there are currently around 150 unique beer styles in the world.

All types of beer, regardless of category, should meet basic quality criteria common to all beers. None should contain obvious fermentation defects, unpleasant mouthfeel, or off-flavors generally considered undesirable.

The world of beer is a vast and endless variety of flavors. Everyone will find something to their liking.

General division

The question of how to divide a beverage as diverse as beer into stylistic groups has been a headache for many experts around the world. Moreover, every country has historically had its own classification. Sometimes, however, it was in contrast to the classifications in other ethnolinguistic circles. The best example is Great Britain, where the meanings of the words ale , beer , stout , and porter intertwined. At times, the meanings of these words also changed.

In today’s post-revolutionary terminology, a division originally derived from Germany is used: top-fermented beers ( ale ) and bottom-fermented beers ( lager ), adapted to our Americanized times. It’s worth remembering that historically, Germans referred to lagers that—as the name suggests—lager, meaning they mature for a longer period of time to allow flavors to develop. This is also how top-fermented lagers (!), such as Kolsch, came into being. From today’s perspective, it’s a linguistic monstrosity.

In modern times, this division has been simplified, and the type of fermentation is the most fundamental source of differentiation between styles. Roughly speaking, all beer styles can be divided into top-fermented and bottom-fermented. Sometimes, wild or mixed-fermented beers are also added as a separate category.

Below I will present more detailed characteristics that distinguish beer types.

Origin

One of the oldest distinguishing features of beer types is undoubtedly their origin. After all, in the aforementioned Germany, the word “ale” referred exclusively to English beers and was not applied to, for example, Hefeweizen, which by today’s standards is certainly an ale. Historically, beer styles are divided into British , German , Czech , Belgian , Eastern European (including Grodzisk and Baltic porter), North American , South American, and Pacific .

These categories are, of course, quite liberal and arbitrary, as, for example, we have to classify Austrian styles, such as Vienna lager, or Dutch styles, such as May bock beer. Some also lump Austrian, Czech, and German styles under another umbrella, called Central European, or even Imperial, styles.

This division does not include Asian or African beers, because apart from mass-produced lagers from China or Thailand (these should be classified as international lagers) – they are still practically unknown in the post-Judeo-Christian civilization.

Era

BJCP distinguishes three eras of brewing: historic , traditional , and new wave . Historic beers are those that are either no longer brewed or only appear occasionally—as curiosities. Burton Ale is a good example. This category also includes beer styles revived by enthusiasts, such as Grodziskie, Sahti, and Lichtenheiner.

Traditional brewing encompasses virtually everything that existed before the beer revolution that began in the late 1970s in the U.S. This category includes classic Belgian styles, including abbey beers, as well as German and Czech pilsners, wheat beers, and traditional English ales.

New Wave beers, in turn, are the children and bastards of the craft revolution: beers heavily hopped with American hops, versions from the Pacific region or South Africa, and modern interpretations of old beer styles .

Power

In terms of strength, beers are divided into session (light), standard , strong , and extra strong . These are very arbitrary boundaries and depend on the region we find ourselves in. However, let’s focus on the contemporary post-revolutionary classification. After all, for an Englishman, a 6% ABV beer would be ultra-strong, while for a Pole, it would be ordinary at best.

As a British man explained to me at the Warsaw Beer Festival , session beers are those you can sip as much as you want in a single session without getting completely drunk. That’s why he criticized our 4.5% ABV Session IPA. He was right, to a degree, as the BJCP lists the sessionable threshold as 4% ABV. However, he forgot that we live in Poland, where my colleague Łukasz once coined the term “session RIS” —a 10% ABV beer that goes down like a light stout. It’s only appropriate, of course, for seasoned beer enthusiasts.

In fact, all beer styles above 9% ABV should be classified as very strong, with a further range of 6-9% for strong and 4-6% for standard. I can’t entirely agree with this. I’d move these boundaries to 4-7%, 7-10%, and 10%+, but my Slavic spirit speaks for itself here.

Style family

Another criterion by which we can distinguish beer styles is their membership in a larger group—a family. Thus, all Pilsners—Czech, German, or American—would belong to the Pilsner family. All IPAs would belong to the IPA family, and so on. We can create many such macrocategories, such as light lagers , abbey beers , amber beers , stouts , porters , bocks , wheat beers , lambics , wild beers , sour beers , and specialty beers not otherwise classified.

This last category is undoubtedly the most interesting for me, as it encompasses all the crazy beer experiments that I love.

Appearance (color and transparency)

In terms of appearance, we can classify beer by color and clarity. The latter is quite simple to define: there are clear , cloudy , or slightly opalescent beers. A much more nuanced criterion is beer color. To define it, we can use several scales common in the beer world: SRM, EBC, or Lovibond.

Any boundaries drawn between these colors will be arbitrary, but certain conventional ranges exist. Starting from the lightest, beer styles are divided into light (straw, yellow, gold), amber (copper, ruby), and dark (brown, black). There are also secondary colors, such as red beers, which owe their color to special malts or a specific composition of dark malts in the grist.

This classification, of course, excludes beers that derive their color from sources other than malt. Good examples include fruit beers (e.g., cherry), vegetable beers (e.g., beetroot), floral beers (e.g., those with the addition of the blue-coloring Clitoria ternatea), and finally, those with artificial coloring.

Taste and aroma

Many factors contribute to aroma, flavor, and mouthfeel. Beer styles can be differentiated by the profile achieved using classic brewing ingredients: water, malt, hops, and yeast. Changing or slightly modifying even one of these components can result in a different beer. This is also worth keeping in mind when brewing at home.

Water profile

Water is roughly divided into soft and hard . The former is more suitable for light, pale beers like pilsner. The latter, conversely, will help achieve the flavors desired in stouts and porters. Modifying water, however, involves not only adjusting hardness but also its appropriate mineralization and pH .

Some styles require a very specific water profile. A good example is the aforementioned historic Burton Ale, which required water with a significantly higher percentage of sulfate ions. This gave the beers from Burton-upon-Trent their distinctive flavor and distinct, harsh bitterness .

There are different schools of thought when it comes to IPA brewing. The first wave, from California, favored a high sulfate/chloride ratio to emphasize bitterness. The newer wave, from New England, sought to balance this balance so that the hop bitterness wasn’t further accentuated by the water profile, and the beer itself was more drinkable and milder in flavor.

Maltiness

Malt is the basic raw material used in brewing beer. It’s from it that the color, body, and depth of flavor come from. Contrary to popular myth, beer isn’t made from hops. They’re merely a flavoring.

Among beer styles , based on malt content, we can distinguish those in which the base malt dominates (Pilsner or pale ale). In flavor, the malt base will merely serve as a foundation for other prominent players – expressive hops or characteristic yeast. Notes that will appear here include grain, bread, or light dough.

The method of malt production influences not only its color but also its flavor profile. As increasingly darker malts are introduced into the grist, the beer will develop notes of toasted bread crust, toast, biscuits, toffee, caramel, chocolate, or coffee. Special malt extraction processes can also produce smoky, smoky, or sour notes.

The influence of malt on defining a beer style primarily lies in its relationship to other flavor sources. Therefore, we speak of sweet , malty , or balanced beers when the accents are shifted roughly halfway toward malt. When hops or other flavors are more important, we use terms derived from other ingredients. It’s also important to remember that sweetness and fullness can—but don’t necessarily—come from malt. In many modern beers, this is achieved through the addition of non-fermentable sugars, such as lactose or maltodextrin.

The use of specialty or very dark malts can also categorize beer styles. Hence, for example, smoked beers or those with roasted flavors.

Hoppyness

The beer revolution is, in fact, a revolution in American hops. Without dry-hopping with highly intense American varieties, the global, mass-scale phenomenon that is craft beer likely would never have existed. Of course, hops aren’t the only thing that makes beer. They’re merely an addition. However, especially among new-wave beer styles, they’re the dominant force.

When classifying beer styles based on hops, we can essentially speak of three categories. The first are those with a negligible hop content. In such cases, we refer to them as derived from other ingredients, such as malty or balanced . However, if hops are the key element in describing a beer style, we can speak of heavily hopped beers (or alternatively, beers with a pronounced hop character) and – somewhat parallel – bitter beers (those with a high hop bitterness).

A pronounced hoppy character should not be confused with bitterness, as these are parallel concepts, intertwined but not identical. This is especially important when describing very contemporary beer styles that emphasize hop aroma while limiting bitterness.

The influence of yeast

Many books and scientific papers have undoubtedly been written about the world of yeast and its impact on beer flavor. After all, even at the most basic stage, we divide beers by type of fermentation—that is, by the yeast used.

Beers with a focus on malt or hoppiness will typically require the use of yeasts that are as neutral and clean-fermenting as possible ( bottom-fermenting ) or those that produce a limited number of esters , giving flavors ranging from fruit to bubblegum ( top-fermenting ). Their levels will also vary in some beers.

However, there are styles where specific yeast flavors are essential. These include the classic Hefeweizen, fermented with a special strain that imparts banana and clove flavors.

The situation is similar with Belgian beers, which use yeasts that produce specific spicy flavors derived from phenols . Yet another category are beers fermented with wild yeasts , bacteria , mixed cultures , or those of unknown provenance.

Other flavors

In addition to the traditional brewing ingredients specified in the Bavarian Purity Law , some styles require the use of specific non-standard additives. Examples include the ubiquitous use of candied sugar in Belgian beers and lactose in milk stouts and other sweetened beers.

Another thing is the variety of fruits, vegetables, flowers, and spices. After all, there’s no witbier without coriander and orange peel , no gose without salt , and no kriek without cherries .

Beer styles are also distinguished based on the flavors obtained as a result of long-term aging of beers in oak barrels – especially after strong alcoholic beverages.

List of described styles

This article is intended to serve as an introduction to the beer styles I cover on my website. Each time I add a new description, I’ll try to include a link to it in this section. So far, the following descriptions have been created:

- Cold IPA

- APA

- Grodzisk beer

- IPA ( history , characteristics , types )

- Bock

- Lager

- Wheat beer

- Piwo wymrażane (freeze-distilled beer, ice beer, eisbock)

- Baltic Porter

- Stout

Not just a foodie, but also a self-taught chef who cooks and tests recipes from around the globe. A traveler and connoisseur of great dishes across countries and cultures. Certified beer sensory specialist. Owner of a contract craft brewery renowned for wild, experimental brews. A former homebrewer with deep know-how in brewing techniques and beer styles. Loves pushing flavor boundaries—both on the plate and in the glass. His motto: “Go big or go home.”